The death of An Sung-ki at 74 is not, by itself, a story with obvious relevance outside South Korea. He was not a Hollywood figure, nor a recognizable name to most American moviegoers. Yet his passing marks the end of a generation that explains how South Korean cinema survived decades of instability long before it became a global cultural force.

An’s significance was never about international visibility. It was about continuity. Over nearly 70 years and more than 170 films, his career ran alongside the modern history of Korean cinema itself. As the industry moved through postwar reconstruction, political censorship, social realism, commercial expansion and eventually global recognition, he remained a constant presence. In an environment where styles, systems and even entire production structures repeatedly collapsed and reformed, that kind of continuity was rare.

For much of the late 20th century, South Korea’s film industry lacked the institutional protections familiar in Hollywood. Political pressure, shifting regulations and fragile financing routinely interrupted careers. Actors were often casualties of these resets. An became an exception, not by dominating box offices, but by adapting without losing credibility, moving between genres and eras as the industry reinvented itself.

His adult career took shape in the early 1980s, when Korean filmmakers began using cinema to confront poverty, urban dislocation and moral uncertainty during rapid industrialization. He emerged as a central figure in socially grounded films that helped reposition cinema as a serious cultural medium rather than escapist entertainment. When the industry expanded in the 1990s, absorbing private capital and pursuing mass audiences, he transitioned again, appearing in war dramas, mainstream comedies and genre films without becoming out of step.

By the 2000s, as Korean films began achieving unprecedented domestic scale and laying the groundwork for later international visibility, An had become an anchoring figure. He appeared in major commercial productions while also lending authority to quieter, reflective films. His presence signaled professionalism and institutional memory at a moment when the industry was accelerating.

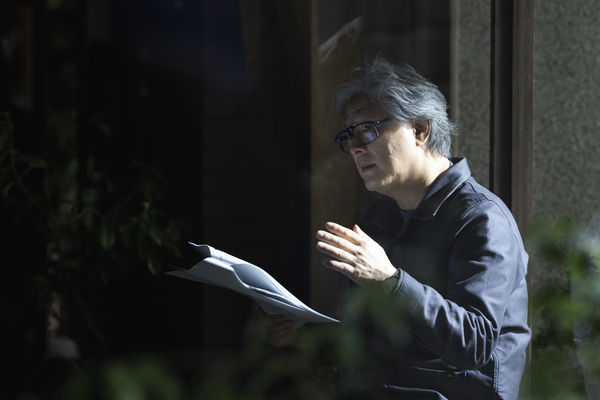

In South Korea, he was often described as a “national actor,” a phrase that does not translate cleanly. It does not mean the most famous or the most profitable. It means trusted. He was a figure audiences accepted as representative across political lines, genres and generations. That trust extended beyond cinema. Beginning in the early 1980s, he served for nearly four decades as the face of a single coffee brand, an unusually long tenure that embedded him into everyday Korean life and reinforced his image as familiar rather than aspirational.

His influence was not limited to the screen. He served as president of the Korean Film Actors Association, participated in efforts to protect domestic film quotas and worked as a goodwill ambassador for UNICEF Korea. These roles reflected a career spent reinforcing the industry’s foundations rather than standing apart from them.

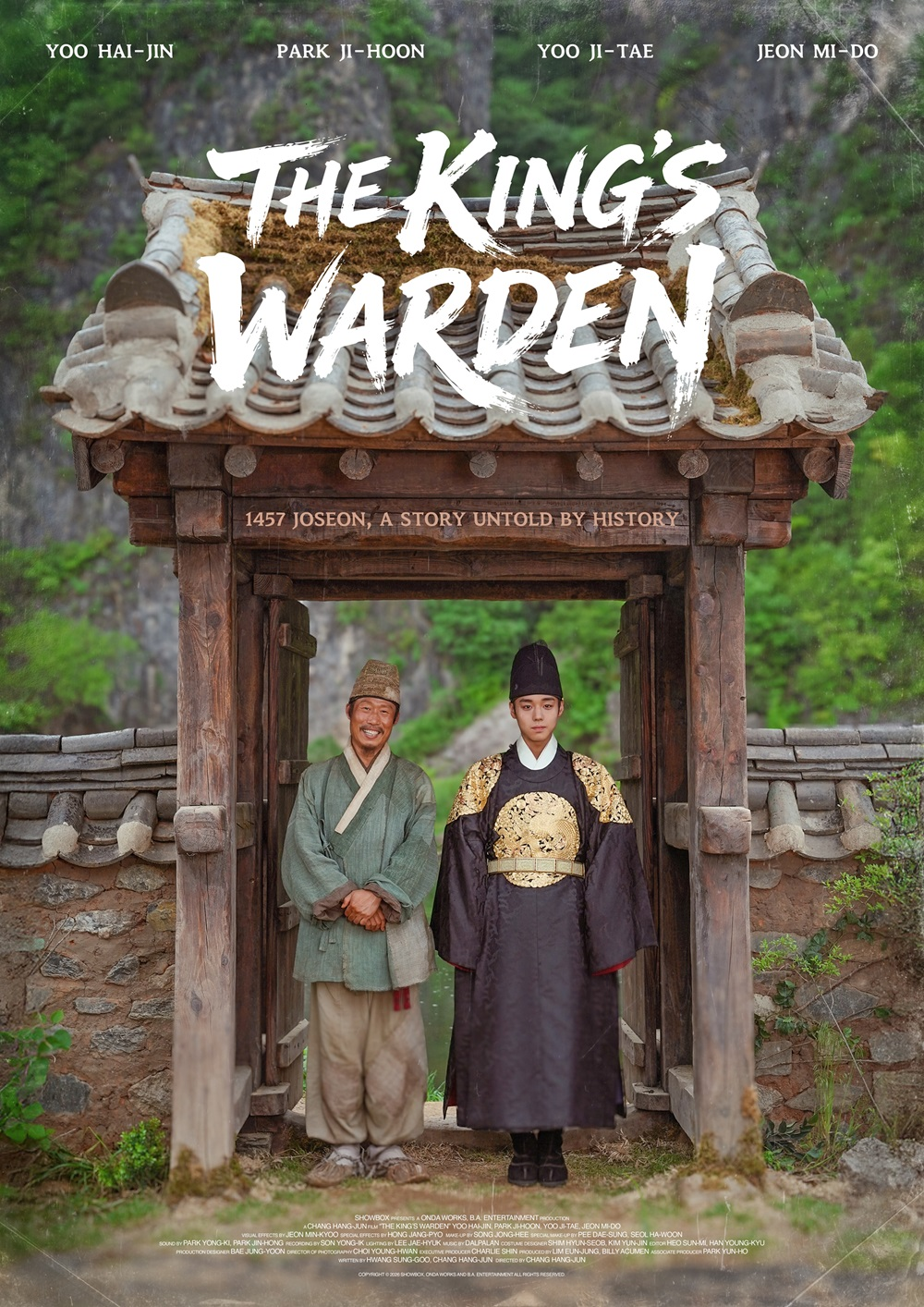

An had been battling blood cancer since 2019 and continued working as long as his health allowed. His final film appearance came in 2023, in a historical epic set during the 16th-century Imjin War, where he played a senior aide rather than a central hero, a role that mirrored his late-career position within Korean cinema.

His funeral is being held as a filmmakers’ funeral, an honor reserved for figures considered integral to the history of the medium. The relevance of his death lies not in celebrity, but in what his career reveals: that the global success of Korean cinema was not built only on breakthrough hits or visionary directors, but also on figures who carried the industry through its most fragile transitions, long before the world was watching.